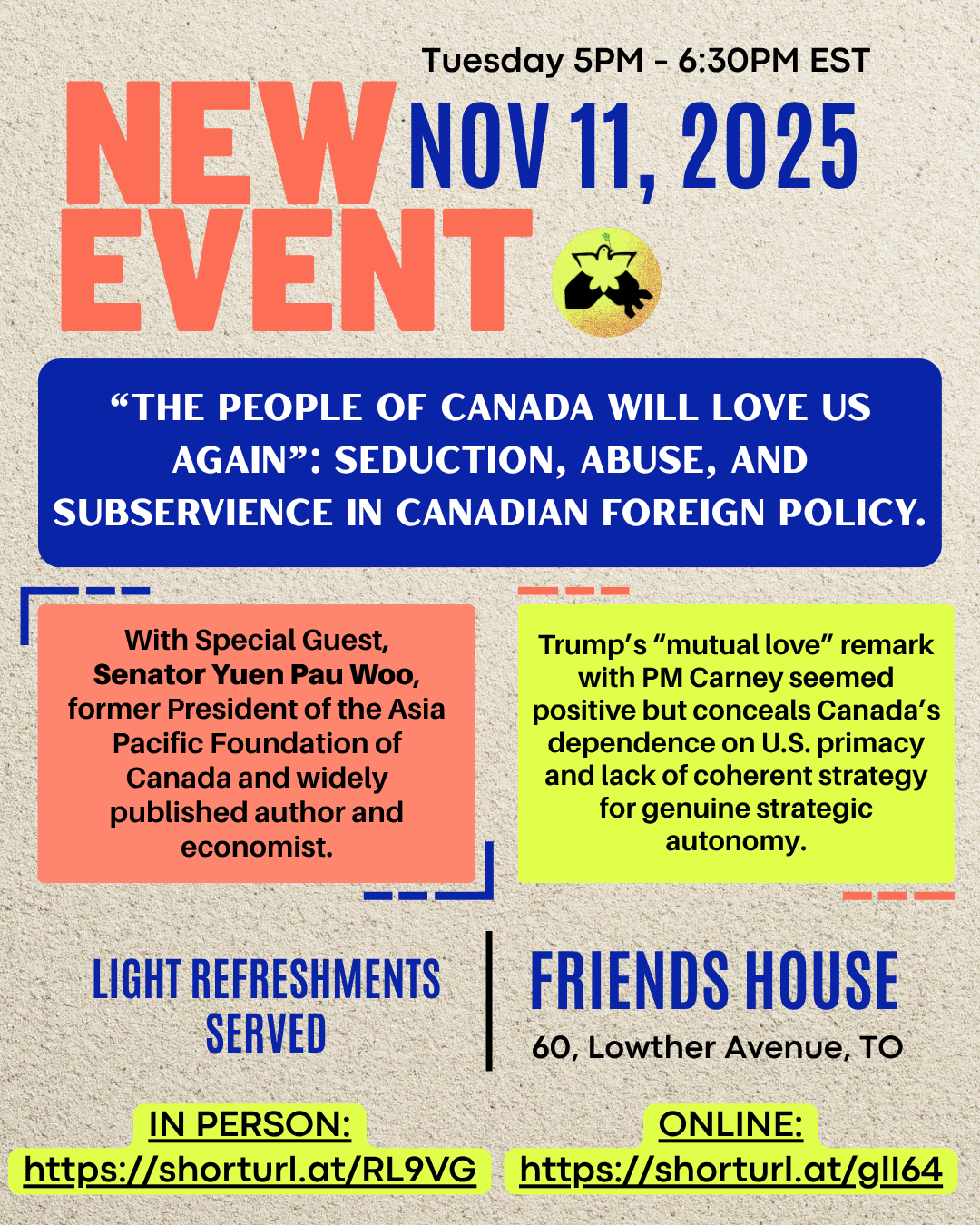

The People of Canada Will Love Us Again: Seduction, Abuse and Subservience in Canada-US Relations

Speech at Science for Peace

Friends House, Toronto

Thank you, Richard Sandbrook, for the invitation to speak at tonight’s meeting of Science for Peace. I note that we are gathered at “Friends House” in Toronto, which I suppose is appropriate for a speech entitled “The People of Canada will Love us Again”. But as you know, the subtitle of my presentation is “Seduction, Abuse and Subservience in Canada-US Relations”, which means I will be talking about distorted views of friendship between Canada and the United States, and in our international relations more generally.

The title of my speech is taken from US President Donald Trump, who said in his meeting with PM Mark Carney on October 7 that “The people of Canada will love us again”. He went on to say: “Most of them still do, I think — they love us.” The operative phrase is “I think”.

We should be familiar by now with the sometimes demeaning, occasionally mollifying, often toxic, and almost always baffling utterances of the US President. His most troubling remark is of course the taunt about Canada as the 51st state and our Prime Minister as a Governor.

It should be clear to everyone that the idea of Canada as the 51st state is more than the musings of a capricious and boorish leader. President Trump’s threats have so far been met by defiance and an outburst of Canadian nationalism. But don’t mistake the response so far as an assertion of Canada’s strategic autonomy. If you look carefully at our appeal to Washington to spare us from tariffs, what we have seen so far is the opposite.

Take the visit of provincial premiers to Washington in early March, at which some provincial leaders pledged to help the United States counter China as a “common enemy”. We have differences with China that we need to work out bilaterally, but to volunteer for service as America’s henchman against the PRC is as self-defeating for our relationship with Washington as it is for our relationship with Beijing.

Many commentators have offered the old American dream of “manifest destiny” and the Monroe doctrine to explain Trump’s 51st state comment. But whereas manifest destiny and the Monroe doctrine of the early 19th century and its 20th century variants were about territorial expansion and influence commensurate with rising American power, in the current context it is about territorial consolidation as a rearguard action against multipolarity. In other words, contemporary expressions of manifest destiny are about the decline of American power relative to the rest of the world. It is the old order fighting to remain relevant, with Canada (and perhaps Greenland) seen by Washington as essential to maintaining the continental remnant of that old order. Early reports on the 2025 U.S. National Defense Strategy (NDS) suggest that it will focus on defending the U.S. homeland and the Western Hemisphere, consistent with the continentalist vision of a manifest destiny that is on the retreat.

Antonio Gramsci, writing from prison between 1930-32, had an observation about the turmoil of his time that would not be out of place for the present circumstances. He said:

"The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum, a great variety of morbid symptoms appear. If the ruling class has lost its consensus, i.e., it is no longer ‘leading’ but only ‘dominant,’ exercising coercive force alone, this means that the great masses have become detached from their traditional ideologies, and no longer believe what they used to believe previously. The crisis creates precisely this situation of great masses who no longer consent to the existing order.

This means that the terrain is open to both new ideological constructions and regressive, reactionary movements. In this phase, one sees the emergence of charismatic figures, demagogues, and attempts to restore authority through coercion rather than consent. The struggle for a new hegemony begins, but in the meantime, a kind of social paralysis can occur, where the old system is incapable of renewing itself, yet the new system is not yet strong enough to take hold."

While many Canadians see the threat of Trump’s tariffs as the most important challenge facing the country, I believe the more important medium to long term test for Canada is in adapting to the rise of a multipolar order that is the obverse of America’s relative decline in the world – navigating the “interregnum” if you will. By this, I mean the growing weight of countries from the “Global South” in the world economy, which is manifesting as the rise of alternate, non-western sources of technological innovation, demand for goods and services, political voice, and soft power. Foremost of all is the People’s Republic of China, which has a larger economy than the United States measured by PPP, has already surpassed the United States as an infrastructure, manufacturing and trading power, and is now a peer competitor in many technological and military domains. It is the only country that appears to have genuine bargaining power to push back successfully against US economic coercion.

As we all know, Trump’s musings about absorbing Canada as the 51st state ignited an upsurge of nationalist sentiment across Canada that in turn ushered in a government that campaigned on the slogan “elbows up” and promised a more independent approach to world affairs. Mark Carney famously said: “At a time of rising global conflict and authoritarianism, there are those who are stepping back from global leadership. Canada believes in open cooperation, in the free flow of good services and ideas. If the United States no longer wants to lead, Canada will”.

And yet, while much of the Canadian foreign policy establishment is now accepting of a multipolar reality, most of the conversation about how Canada responds to this emerging new order is grounded in the old one. Yes, we recognize the damaging self-interested turn of the United States, but we continue to premise our foreign policy choices on American hegemony. We see the Russian threat to Europe and pledge our support for a beleaguered Ukraine but seem oblivious to a growing chasm in trans-Atlantic solidarity and the fundamental impotence of European states (never mind Canada) to bring about peace in Ukraine. We are rightly alarmed by threats to the world economy from protectionism and the evisceration of ODA but are looking to the G7 as a solution to global challenges that are not remotely within the power of that enfeebled organization to address. We talk about increasing defence spending to meet the demands of NATO even as the alliance is headed for a radical restructuring that surely will be centered on European strategic autonomy, to the exclusion of North America. And our response to the genocide in Gaza is made with one eye on the United States and the other on balancing domestic politics, rather than on adherence to international law.

These are some of the Gramscian “morbid symptoms” that have been unleashed during the interregnum, and the current debate on the future of Canadian policy is largely oblivious to them.

By way of context, it is important to recognize that a multipolar world has emerged in part because of “globalization”, or more specifically the liberalization of trade and investment which has provided opportunities for developing countries to insert themselves into value chains and to export products and services directly or indirectly to industrialized economies. Participation in the global economy in turn allowed the global income gap to narrow, both in terms of median national income but also among individuals. In this sense, it is important to note that some of the western backlash against globalization is not simply an effort to minimize the excesses of unfettered trade and investment and its adverse impacts domestically but is also, I believe, an unspoken attempt to roll back the diffusion of power and influence outside of the West.

Hence, the now preferred approach to workforce adjustment due to trade disruption is not income support and retraining, but reshoring of industries and provision of state subsidies for businesses that would not otherwise be competitive. Instead of encouraging second and third sourcing of manufactured goods in developing countries that could use the additional investment, the US and its allies want to “shorten” supply chains, “reshore” manufacturing, work with only “like-minded” trading partners, or – particularly in the case of the United States – to extort foreign investment into the US. The backlash against “neoliberalism” and “globalization” across the western world has made this kind of nativist economic policy easier to pursue, but it will make it more difficult for developing countries to reduce the income gap with the west and will leave them worse off.

Well before Trump, Canada has been pursuing a foreign policy that tries to address important international issues without properly recognizing and accommodating the rise of emerging powers. It has done so by privileging above all its relationship with the United States. Our acquiescence to tough conditions in CUSMA, and the approach we took to protect our interests in the US Infrastructure, Inflation Reduction, and CHIPS bills (as well as Buy America policies in general) says a lot about how much Ottawa had resigned itself to a continentalist economic vision. While I appreciate that the mantra today is diversification of our trade away from the United States, and I hope that we succeed in that effort, there are powerful elite networks, ideological alignments, and entrenched interests that will keep pulling us back into the American orbit.

As you are all aware, negotiation on the Section 232 and IEEPA tariffs, as well as other border disputes with the US, have been paused since the advertisements in the US launched by Ontario. The special tariffs on aluminum, steel, and softwood lumber are causing significant hardship in those sectors of the Canadian economy. And the uncertainty around new tariffs and other forms of economic coercion are sapping business and consumer confidence.

Recent comments from PM Carney indicate that the government expects the current suite of US tariffs to remain, with no breakthrough in the offing. That suggests to me the new focus for any resumption of negotiations will be on the mandatory review of the USMCA that is scheduled for 2026.

The way the review works is that each party must indicate at the end of each six-year anniversary if it wants to continue to be party to the agreement. The next anniversary is 1 July 2026. If all three countries agree, the agreement is in effect for another 16 years. If one or more party declines, a ten-year countdown to the termination of the agreement is set in motion. While there is a seeming orderliness to this process, any triggering of the termination clause will have an impact well before ten years. In practice, the review mechanism is a way for the parties (chiefly the United States) to use each six-year interval as an opportunity to renegotiate the deal, using withdrawal as a threat. That is almost certainly the intention of President Trump in the 2026 review. But even in the absence of this review mechanism, the United States has not been reticent in circumventing the provisions of USMCA by invoking Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act or the IEEPA and he could very well continue to do so under a renewed agreement. In less than 8 months, Mexico and Canada could find themselves in a situation where the benefits and protections of USMCA have been further eroded either through coercive renegotiation of or blatant disregard for the agreement.

And yet, there is an important strand in Canadian elite opinion that is advocating for even deeper North American integration as a response to the Trump tariff threat. Sometimes framed as a further evolution of NAFTA and at other times seen more narrowly as a Canada-US only project, this view has been described as “Fortress North America”, a “Grand Bargain” or an “Economic and Security Pact” that is designed to boost competitiveness and reduce dependence on China, especially for critical minerals. One prominent proponent of the Grand Bargain puts it this way: “Rather than engaging in another round of asymmetrical USMCA renegotiation, Canada could push for a Grand Bargain – a more ambitious, comprehensive negotiation that incorporates many unresolved bilateral issues and shared opportunities. Such an agreement could include areas like critical minerals and energy, border and continental security, defense spending, softwood lumber, food and water security, cross-border infrastructure, and regulatory alignment”.

Now, I am not so naïve to think that we can counter the tariff threat from the US without some sweet talk along the lines of “Fortress North America” but there should be no illusions about this kind of placation, which will take us down the road towards a form of the 51st state, whether we like it or not. The reality is that reciprocal tariffs hurt Canada more than they hurt the United States and the longer this tit-for-tat war goes, the more open Canadians will be to a version of the North American fortress.

Of course we won’t call it the 51st state. But common external tariffs in certain key sectors, possibly a kind of customs union, is within the bounds of possibility. Perhaps even a currency arrangement which cedes control of monetary policy to the Federal Reserve. Very few people in Canada are talking about these scenarios now because we are still in the rage or “elbows up” phase of our blowup with the United States, but I am certain that if the US keeps up its campaign of economic coercion against Canada, there will be a serious debate in this country about moving in the direction of the 51st state. We will see political and cultural divides in this country that make debates about Quebec independence seem like a squabble over pocket change.

To be clear, I am on the side that resists a closer economic union with the United States that reduces our strategic autonomy in the world. For those who share my view, the best we can hope for at this stage is that the storm will pass before North American integrationist forces in Canada gather overwhelming strength. Perhaps a sharp and prolonged downturn in financial markets will force President Trump to moderate his approach. Or perhaps a different America will emerge a year, or three, following the mid-term and Presidential elections in 2026 and 2028 respectively – one that respects the right of Canada to have some strategic autonomy in the world even as our economy remains closely tied to the United States. But I am not optimistic. For Canada to pursue a degree of strategic autonomy in its international relations will require some amount of beneficence on the part of the United States, never mind respect. I am not sure America, under any administration, is much interested in beneficence. The reality is that the United States is a declining hegemon and one that increasingly recognizes its diminishing influence outside North America. It is for that very reason that the United States will not also seek to diminish its influence within North America. On the contrary, the secular forces at play will compel it to go in the opposite direction.

I am a member of the Senate Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and we recently had hearings on Canada-US trade disputes. We have heard from industry leaders representing major business organizations such as the APMA, CAMA, CCC, and CME and, while every one of those witnesses decried the unjustified and self-defeating nature of the US tariffs on Canada, my sense of their bottom line is that they would be willing to de-couple to some extent with the rest of the world if the Americans would guarantee market access and a reasonable amount of business predictability for our firms to operate in the US. The pathway to this new equilibrium is what our business leaders would call greater “regulatory alignment” with the United States, which on the face of it sounds benign, even desirable. There was a time when regulatory alignment meant cutting duplicative rules, streamlining border procedures and adopting common international standards – less a “fortress” defending against marauding foreign invaders than a way of building competitiveness for global markets. Today, regulatory alignment is wielded by Washington as a form of economic coercion to divert investment into the United States or as a poison pill to discourage trade with adversaries, notably China. We saw powerful evidence of such in the recent US-Malaysia and US-Cambodia deals signed when Trump was in Kuala Lumpur.

Much of corporate Canadian thinking on regulatory alignment is premised on a United States that respects the comparative advantage of its neighbours and does not seek to induce or force manufacturing in those countries to relocate to the United States. It also presumes that a North American production platform is outward oriented and interested in being competitive in fast growing markets such as Asia and Africa, as opposed to being a largely closed continental market with the US at the center and Canada/Mexico on the periphery. Depending on the size of external tariffs and the nature of internal policies driven by the lead economy, a Fortress North America could be extremely competitive in global markets, or it could be moribund and sclerotic inside a protective economic bubble. On the current record, it seems fanciful to imagine that the United States would not seek to privilege its own interests above those of Canada and Mexico in any Grand Bargain or Fortress North America. It is precisely this kind of center-periphery economic dependency in North America that I believe President Trump is seeking to cultivate.

After all, what is Canada’s value as a 51st state if it doesn’t provide net benefits to the 50 other states (or the favoured states among the 50)? If Canada can in fact be a source of critical minerals for North American supply chains, will it only supply the clean energy and raw materials that the US needs, or is there room for Canada to be involved in valued-added activity? And if North American tariffs are set at levels that stifle competition and inhibit innovation, which external markets will North American products be able to access competitively? The case of EVs is an excellent example, where Fortress North America proponents imagine developing a world-class EV supply chain behind high tariff walls and expect to produce vehicles that can compete with EVs from other countries (notably China) that are already years ahead of North American products. It is not that a Fortress North America will mean the end of trans-Pacific ties, but it will almost certainly mean a trans-Pacific relationship that is premised on US geopolitical priorities.

An alternative vision would see Canada protect its access to the North American market to the extent that it can but actively seek new trading relationships in Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Canada is fortunate to have trade agreements with the EU and with many Asian countries through the CPTPP. Ottawa is also in the late stages of concluding a deal with ASEAN. This idea of economic diversification has been a long-standing staple of Canadian trade policy, with periodic bursts of political energy seeking to spur Canadian businesses to venture to markets beyond North America. We are currently in one of those periods and are witnessing what is arguably the most vigorous effort to pivot away from the United States since the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement.

For all the emphasis on not becoming the 51st state, however, Canada’s response to the US tariff threat and its effort to diversify to other markets, especially in Asia, is shaped by 51st state thinking. At the core of the plea that Canadian political and business leaders are making to Washington DC is the idea that we are still their most trusted friend and ally, and that if only they understood it and embraced Canada more closely, we would have a better and more sustainable economic relationship. It is the international relations equivalent of battered spouse syndrome.

It was the reflex of a battered spouse that led to the imposition of a 100% tariff on Chinese EVs in lock step with the Americans, without any meaningful investigation of Chinese state subsidies and dumping. I learned recently from industry insiders that the Americans weren’t even aware of our early Christmas gift, which partly explains why we got no credit for it. Ottawa not only did not get the reward it had hoped from the United States for taking this action but rather attracted the ire of the Chinese, which slapped retaliatory tariffs on Canada canola, pork, and seafood products. It was the worst of both worlds.

Canada’s recent engagement in Asia has much the same quality. The so-called Indo-Pacific Strategy is premised on preserving US primacy and advancing American priorities in the region, especially when it comes to China. Canada’s IPS is essentially an Asia minus China strategy. It stems from the very framing of the IPS document, which goes out of its way to describe China as a “disruptive power”. This kind of language is not found even in the IPS documents of East Asian countries for which Chinese disruption is real and consequential. That Canada would feel the need to include this phrase in its IPS says a lot about US influence on Canadian strategic thinking. Insofar as “disruption” to the Canadian economy is concerned, it should be obvious that the threat is much closer to home, but to say as much in a public strategy document would be gratuitous and counterproductive.

There is now universal agreement on the need to diversify our trade and investment so that we are not so dependent on the United States. Much of the focus for trade diversification is on the Asia Pacific region, building on the CPTPP and other trade agreements that we have across East and Southeast Asia. All of that makes sense. What does not make sense is the idea that we should diversify to all of Asia, but not China, as some analysts and politicians are calling for. This is insanity. It is bad enough that our access to the world’s largest market has been impeded, perhaps for a very long time. Are we also going to deny ourselves access to the world’s second largest market? Set aside for a moment that Trump may talk tough but continue to encourage US firms to make money in China, as he did in his previous administration. How are we going to prepare for a new order by shunning the one country that will, for better or worse, be a major player in that changed environment?

Canada-China diplomatic relations have always operated in the shadow of Canada-US ties. This was as true when Diefenbaker decided to sell wheat to China in the face of opposition from JFK, as it was when Chretien agreed to grant China Most-Favored Nation (MFN) status, contrary to the position taken at the time by the Clinton administration. It is still the case today, only more so because of heightened competition between the United States and China that is spilling over to Canada and other countries that are caught in between. On the one hand, US policymakers are dismayed that economic engagement with China has not resulted in a relaxation of political control on the part of the CCP, or greater openness to foreign competition in the Chinese market. On the other hand, the Chinese leadership, especially since the advent of Xi Jinping, has become more self-assured, even cocky, in its assessment of national economic and military capabilities and accordingly, more assertive in the defence of its policies domestically and abroad. This has all the hallmarks of great power competition, with its attendant risks for each side as well as for third parties, as the history of power transition will attest. The reality is that strategic competition between China and the United States will last decades, and that as the contest deepens, the interests of each side will increasingly take precedence over the views and preferences of third countries.

The question, accordingly, is how to position Canada in the decades-long struggle for economic and technological supremacy between the US and China. The answer is not to retreat into a Fortress North America.

I understand the reasons for Canadian aversion to China, but the PRC is not, as some ministers and MPs have said, an “existential threat” to Canada in the way that the United States is today. The instinct to demonize China is deeply ingrained in the Canadian political class, and I see it on a regular basis in Ottawa. And I believe we have taken our cues in the way we see and treat China largely because of American prompting and pressure. The increase in research security screening at Canadian universities is a good example, as is the recently completed public inquiry on foreign interference.

I have spent years calling on the Canadian government to put more focus on Asia and I applaud the stepped-up political and economic attention on the region that has come with Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy. The increase attention to the region, especially ASEAN, is especially noteworthy but the reasons for Canada to engage more deeply with India, Southeast Asia, Japan, and Korea should be based on the intrinsic qualities and potential of these markets rather than as an alternative to engaging with China or as a way of containing China’s economic rise. To do the latter would be to align with US priorities, which is counterproductive for Canada’s ambitions in the region, given that most Asian countries are going in a fundamentally different direction from the United States.

To summarize: Canada is once again faced with the question of whether its economy is too closely tied to the United States and what to do about it. The growing public distrust of the US, together with an outburst of economic nationalism and Ottawa’s (re)commitment to trade diversification, would suggest that we are on our way to redefining our place in North America – one that is as far away from that of a 51st State as can be imagined. However, our efforts to contain the damage from the Trump tariffs carry in them the very seeds of deeper integration with the United States, and – ominously – a measure of decoupling from the world. Deeply rooted political instincts combined with powerful business interests and longstanding people-to-people ties shaped by the American imperium constitute a dense set of connective tissue of Canada-US relations that will be difficult to relax, let alone trim. And the persistent application of US economic coercion against Canada – coupled with occasional acts of contrition, affection and kindness – will incline many Canadians to choose to stay in a lop-sided (dare I say abusive) relationship. The 51st state problem will be with us for some time yet.

Thank you.