Reflections on Exclusion: An Exhibition on the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923

Preface

This exhibition marks the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923, also known as the Chinese Exclusion Act. The exhibition features Chinese Immigration Certificates (CI’s) issued before and during the period of Chinese exclusion, as well as official documents that trace the passage of the Act through the House of Commons and the Senate, to Royal Assent. The purpose of the exhibition, which is mounted in concourse of the Senate of Canada Building, is to remember the individuals and families who suffered because of government-sanctioned exclusion, and to acknowledge the role of the Parliament of Canada in passing this racist law. It is a reminder of the need to be vigilant about modern forms of exclusion in our society and the role of parliamentarians in never again permitting such laws.

About the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923

The Chinese Immigration Act, 1923 was the culmination of a series of racist laws passed by the Government of Canada as early as 1885. The Act was seen as the necessary means to accomplish what the head tax was not able to accomplish. For 24 years until its appeal, Chinese were not allowed to come to Canada except for a few small exceptions. In addition, Chinese already in the country were forced to register within one year of the coming into force of the Act. Failure to register would have led to imprisonment or fines, or both, as well as threat of deportation. Even after registering, Chinese in Canada would face a constant threat of harassment and investigations as to whether they were legitimately in the country. The Act inflicted fear, violence, and trauma, and had a profound impact on the Chinese Canadian community. It separated families for decades and created a sense of exclusion and discrimination that persisted long after the Act was repealed in 1947. This policy also contributed to the stigmatization of Chinese Canadians and continued reinforcement of stereotypes about Chinese people.

The documents exhibited show the passage of the legislation through the House of Commons, the Senate, to Royal Assent.

The collage of portraits of those registered by the Act gives voice and representation to a small portion of those registered beyond the bureaucratic cataloging system. The collage seeks to honour them and allows us to see their faces in a new, reflective light.

The poster on Chinese Immigration, written in English and Chinese, was a notice to those of Chinese origin or descent that they had to register. The notice includes the locations for designated individuals to register and the requirements for registration.

“Uncovered Acts” by artist Don Kwan, uses mixed media to give a contemporary reflection and response to the Act. The images are from various sources and the Chinese Immigration Act, 1885 and 1923: The Heathen Chinese in British Columbia, by artist James L. Weston 1879 (Illustration), Canada’s Founding Fathers and artwork / portrait of the artist’s mother and his grandmother.

The original Chinese Immigration Certificates of the Fong Sisters and their short biographies provided by Timothy Stanley allows us a more complete picture to the lives behind the identification numbers and faces.

Appreciation

This exhibition would not have been possible without the support of the Office of the Speaker of the Senate of Canada; Office of the Black Rod; the Chinese Canadian Museum (Vancouver); Catherine Clement, curator of "The Paper Trail to the Chinese Exclusion Act"; the Senate of Canada Archives; Action! Chinese Canadians Together; the Canadian Museum of History' the Library of Parliament; Library and Archives Canada; Dr. Timothy Stanley; Offices of Senator Yuen Pau Woo and Senator Victor Oh. Thank you!

Curator

Jiaqi Wu

About the exhibited items

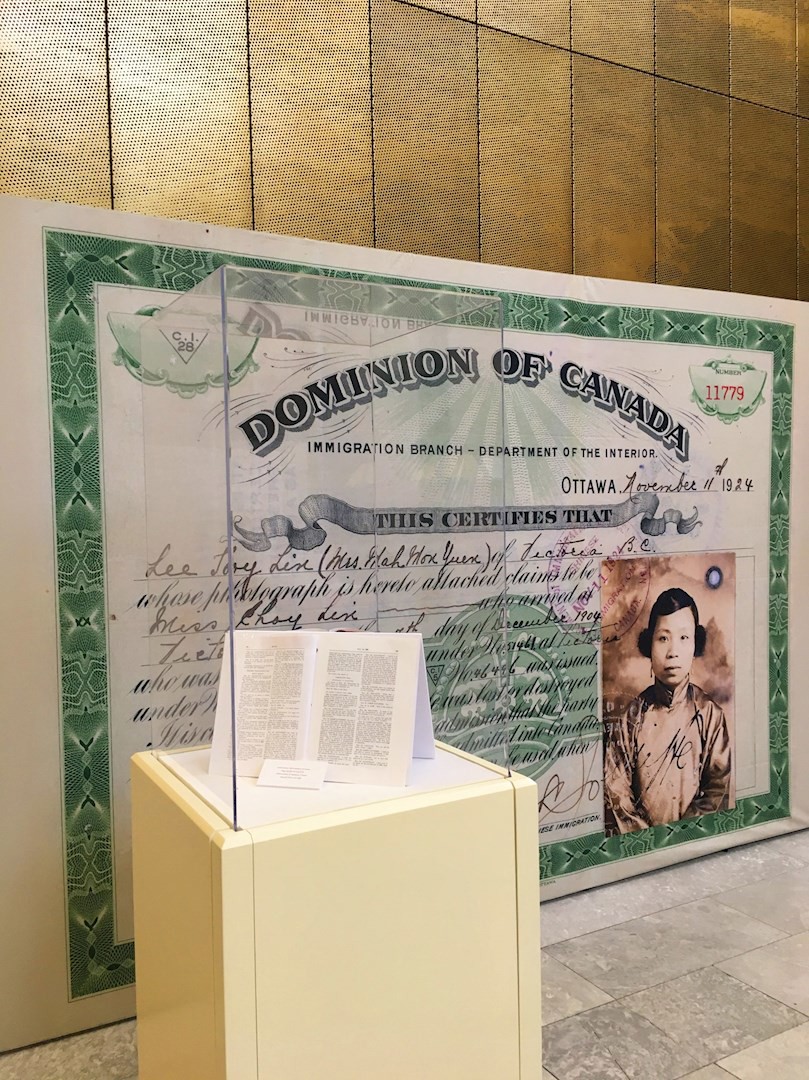

The four enlarged reproduction certificates bring us into direct confrontation with our past; our gaze is called upon to reflect on that tragic period. Notice the variations in detail like the location of issue, colour of the borders, and the varying CI edition numbers found in the upper corner of the CI. The CI document went through various updates and transformations during the course of its usage. All of them share in common the requirement that a head and shoulders photo be attached to the document.

C.I.5: new legislation brought in to control Chinese immigration also spawned the first-ever entry document for Chinese called a C.I.5 certificate. The C.I.5 document was issued to every Chinese immigrant, whether they were required to pay the head tax or not and was used from 1885 – 1911. (Name: CHOW Shung, Ottawa, Ontario)

C.I.30: after 1912, Chinese immigrants who were exempt from paying the head tax, were issued a C.I.30 when they arrived. This certificate had a brown border with the photograph of the bearer. (Name: MAH Foo Tong, Bashaw, Alberta)

C.I.45: was created in 1923, it was issued mainly to the first generation of Chinese born on Canadian soil. (Name: CHONG Ham Way, Nanaimo, British Columbia)

C.I.28: if a Chinese person who had a C.I.5 claimed the certificate had been lost or destroyed or stolen, they were issued a “replacement certificate” called a C.I.28. It was also green and contained the owner’s head and shoulders photograph. 2 (Name: LEE Toy Lin, Victoria, British Columbia)

Looking forward

“Reflections on Exclusion: An Exhibition on the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923” aims to illuminate a dark chapter of our past through the curation and presentation of official documents, a contemporary artistic response to the injustice of the Act, and a collage of faces which gives recognition, respect, and space to those once diminished to a serial number and CI paper. Presented in the Senate of Canada, where the Chinese Exclusion Act received Royal Assent, the faces in the collage are finally visible, and presented as dignified Canadians who are no longer excluded. We hope the exhibition is an opportunity to reflect on this and other examples of exclusion in Canadian history, and to reject all modern forms of exclusion.